Leading from the Ground Up: Ann Chen on Community, Innovation, and Digital Access

This interview explores Ann Chen’s journey as a settlement language training instructor and team lead at KEYS in Kingston, Ontario, and her evolution as an innovator in technology‑enhanced language learning. She describes KEYS as a community‑based, integrated service hub where employment, settlement, and language programs reinforce one another, with language serving as the foundation for social connection, work, and community participation.

Generative AI was used to help organize and edit the original interview transcript. It helped break long answers into shorter sections, add clarifying questions, and improve readability, while keeping the interviewee’s words, meaning, and perspective intact.

Introduction

Rob

Ann, thank you for taking the time to talk with me today. To start us off, could you describe KEYS for readers who may not be familiar with the organization – what it does, who it serves, and how language training fits into its overall mission?

Ann

KEYS is a community-based organization in Kingston that functions very intentionally as a kind of one-stop shop for newcomers. It’s both an employment centre and a settlement services provider, and since 2016 it has also been a RAP centre, supporting government-assisted refugees. What makes KEYS distinctive is the co-location of services: employment, settlement, and language training are not siloed but designed to reinforce one another.

From a language training perspective, that integration is extremely powerful. Our LINC-ESL clients benefit from immediate access to employment services – résumé development, career counselling, job search support – while employment and settlement teams benefit from the fact that clients are simultaneously developing the language and skills they need to participate fully in Canadian society.

From a language training perspective, that integration is extremely powerful. Our LINC-ESL clients benefit from immediate access to employment services – résumé development, career counselling, job search support – while employment and settlement teams benefit from the fact that clients are simultaneously developing the language and skills they need to participate fully in Canadian society.

Rob

So language training isn’t operating in isolation – it’s part of a broader ecosystem of supports.

Ann

Exactly. The organization’s mission captures that well. KEYS focuses on three core ideas: connected people, decent work, and inclusive communities. Language is foundational to all three. Without language, people can’t connect, can’t access meaningful work, and can’t participate fully in community life.

The Chinese Restaurant Workers Project: Origins of a Practice

Rob

Before you came to KEYS, you were already doing innovative work with newcomers. I’d like to go back to that early project you often reference – your work with Chinese restaurant workers in Kingston. How did that begin?

Ann

That project really started when I first arrived in Kingston. I was born and raised in Taiwan and later pursued graduate studies in the UK in second language education. My academic background was very theoretical, and when my husband accepted a position at Queen’s University in 2008, I found myself at a crossroads. The global financial crisis meant there were hiring freezes everywhere, but it was also an opportunity for me to reflect on what kind of work I really wanted to do.

I was a newcomer myself, navigating a new country, and I became interested in how immigrants find their footing – how they build lives in unfamiliar places. At that point, I didn’t even know that “settlement language training” was a field. I just knew I wanted to work with immigrants and language in a way that was practical and meaningful.

I was a newcomer myself, navigating a new country, and I became interested in how immigrants find their footing – how they build lives in unfamiliar places. At that point, I didn’t even know that “settlement language training” was a field. I just knew I wanted to work with immigrants and language in a way that was practical and meaningful.

Rob

And that curiosity took you into the community directly.

Ann

Yes. Through the local Chinese Association, I started meeting Chinese restaurant workers across Kingston. People suggested restaurants I should visit, and when I went, I met many newcomers who had been living in Kingston for years but spoke very little English.

What struck me most was how small their world actually felt. Many lived in dormitory-style housing one block off Princess Street, walked to work in groups, worked long hours, and socialized almost exclusively within their own community. Some had lived in Kingston for over three years and didn’t even know the name of Princess Street, despite crossing it every day.

What struck me most was how small their world actually felt. Many lived in dormitory-style housing one block off Princess Street, walked to work in groups, worked long hours, and socialized almost exclusively within their own community. Some had lived in Kingston for over three years and didn’t even know the name of Princess Street, despite crossing it every day.

Rob

That’s a powerful image – being physically present in a city but not really inhabiting it.

Ann

Exactly. It made me realize that language barriers were not just limiting individual opportunity; they were also limiting the city’s ability to benefit from the presence of these residents. People wanted to learn English, but traditional classroom models didn’t work for them. Their schedules were long and irregular, and on days off they often travelled to Toronto to access familiar services because they didn’t know what was available locally.

So I started asking myself: what kind of language learning would actually fit into their lives?

So I started asking myself: what kind of language learning would actually fit into their lives?

Rob

And your answer involved technology, even at that early stage.

Ann

Yes, although at the time I didn’t think of it as “edtech” or innovation. It was just problem-solving. I realized learning had to be portable. Something they could access while walking to work, cleaning dishes, or riding a bus.

I began creating audio recordings and simple video content based on my background in second language acquisition. I built a wiki page and uploaded materials there. Students listened on their phones and gave me feedback. We met once a week on their day off to practice, reflect, and adjust.

That experience was transformative for me. I saw tangible growth in learners, and I felt a deep sense of purpose. It was also when I realized that language learning in settlement contexts is never just about language – it’s about housing, childcare, healthcare access, employment, and social belonging.

I began creating audio recordings and simple video content based on my background in second language acquisition. I built a wiki page and uploaded materials there. Students listened on their phones and gave me feedback. We met once a week on their day off to practice, reflect, and adjust.

That experience was transformative for me. I saw tangible growth in learners, and I felt a deep sense of purpose. It was also when I realized that language learning in settlement contexts is never just about language – it’s about housing, childcare, healthcare access, employment, and social belonging.

From Grassroots Innovation to Avenue Leadership

Rob

You’ve clearly been integrating technology into your teaching from the very beginning. How did that evolve into your later engagement with Avenue and formal learning management systems?

Ann

The evolution was gradual and very context-driven. During the pandemic, like many organizations, KEYS had to pivot quickly. We relied on tools like ESL Library, Google Classroom, and Zoom. These were practical solutions at the time, but as we started thinking about sustainability and long-term practice, it became clear we needed a more coherent framework.

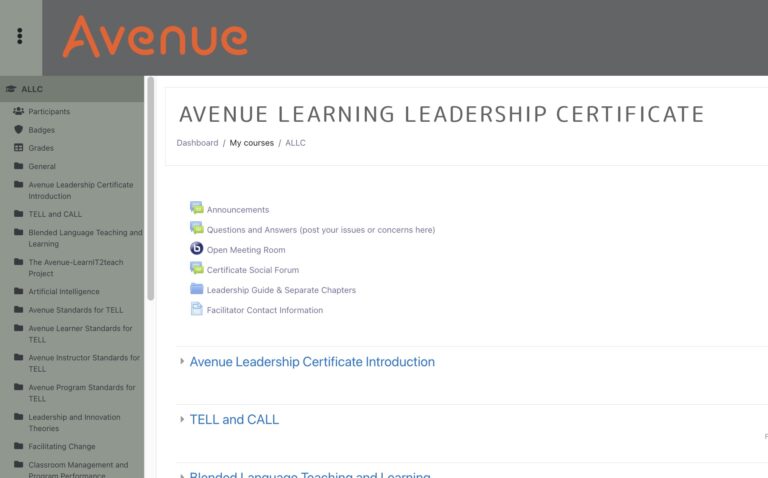

That’s where Avenue came in. What really distinguished Avenue for us wasn’t just the platform itself, but the professional learning structure around it. The staged teacher training created a shared language and a developmental pathway.

KEYS was very supportive. The organization subsidized Stage 1, Stage 2, and beyond. At this point, most of our LINC-ESL instructors are enrolled in Stage 2, and some are working toward completing Stage 3.

That’s where Avenue came in. What really distinguished Avenue for us wasn’t just the platform itself, but the professional learning structure around it. The staged teacher training created a shared language and a developmental pathway.

KEYS was very supportive. The organization subsidized Stage 1, Stage 2, and beyond. At this point, most of our LINC-ESL instructors are enrolled in Stage 2, and some are working toward completing Stage 3.

Rob

What difference did that make inside classrooms?

Ann

You still see a lot of in-person interaction – that will always be central – but now technology is embedded rather than occasional. Teachers project Avenue lessons, students access materials online, and there’s continuity across classes. We still use tools like Google Classroom and ESL Library, but Avenue has become the anchor.

Importantly, it’s also changed how teachers collaborate. With shared courses and sandbox environments, coordination across classes is easier, especially for multi-registered students. Instead of long email chains, teachers can simply say, “We’re in this unit, at this activity – continue from here.”

Importantly, it’s also changed how teachers collaborate. With shared courses and sandbox environments, coordination across classes is easier, especially for multi-registered students. Instead of long email chains, teachers can simply say, “We’re in this unit, at this activity – continue from here.”

Leadership, Identity, and Change from the Ground Up

Rob

You’ve described yourself as an innovator, but innovation doesn’t happen in a vacuum. What kind of leadership has been required to support technology-enhanced learning at KEYS?

Ann

For a long time, my influence was limited to my own classroom. I kept asking myself: if something works here, how can it work elsewhere? What does it take to scale good practice?

I didn’t have an administrative role, so I struggled to articulate what kind of leadership I could exercise. That changed when I enrolled in the Avenue Learning Leadership Courses. They gave me not just ideas, but vocabulary – terms like “change agent,” “digital navigator,” and “diffusion of innovation.”

I suddenly had a framework for what I had been doing intuitively. I realized leadership doesn’t have to be top-down. Innovation can emerge from the ground up, if you can articulate a vision and build trust.

I didn’t have an administrative role, so I struggled to articulate what kind of leadership I could exercise. That changed when I enrolled in the Avenue Learning Leadership Courses. They gave me not just ideas, but vocabulary – terms like “change agent,” “digital navigator,” and “diffusion of innovation.”

I suddenly had a framework for what I had been doing intuitively. I realized leadership doesn’t have to be top-down. Innovation can emerge from the ground up, if you can articulate a vision and build trust.

Rob

And that coincided with a formal leadership role.

Ann

Yes. Shortly after completing the introductory leadership course and while I was enrolled in the advanced course, I stepped into the LINC-ESL Team Lead role. The timing was perfect. My leadership course capstone project aligned directly with organizational priorities around digital access, virtual services, and reducing barriers for learners.

What I’ve learned is that leadership requires vision, but also translation. You have to communicate across roles – teachers, digital specialists, administrators – and help everyone see how their work connects to learner outcomes.

What I’ve learned is that leadership requires vision, but also translation. You have to communicate across roles – teachers, digital specialists, administrators – and help everyone see how their work connects to learner outcomes.

Community of Practice and Local Innovation

Rob

You’ve spoken very strongly about collaboration. How does Community of Practice factor into innovation at KEYS?

Ann

It’s essential. Technology-enhanced Language Learning doesn’t work if it’s just one enthusiastic teacher. Learners have to be prepared, teachers have to be supported, and administrators have to understand the why – not just the how.

Our tablet rollout is a good example. We had over a hundred tablets originally purchased for settlement services during the pandemic. Rather than letting them sit unused, we developed a shared plan to integrate them into classrooms. That required collective problem-solving: identifying essential digital skills, aligning them with language outcomes, and sequencing learning so students could transition seamlessly between in-person and digital environments.

Those conversations – sometimes messy, sometimes slow – are where real learning happens. A Community of Practice creates psychological safety. Teachers feel supported in experimenting, troubleshooting together, and learning from one another.

Our tablet rollout is a good example. We had over a hundred tablets originally purchased for settlement services during the pandemic. Rather than letting them sit unused, we developed a shared plan to integrate them into classrooms. That required collective problem-solving: identifying essential digital skills, aligning them with language outcomes, and sequencing learning so students could transition seamlessly between in-person and digital environments.

Those conversations – sometimes messy, sometimes slow – are where real learning happens. A Community of Practice creates psychological safety. Teachers feel supported in experimenting, troubleshooting together, and learning from one another.

Rob

It sounds very much like distributed leadership in action.

Ann

Absolutely. I set a vision, but the path to that vision is co-constructed. Different people bring different perspectives, and that diversity strengthens the outcome. When people feel ownership, innovation becomes sustainable rather than imposed.

Closing Reflection

Rob

Ann, this has been an extraordinary conversation. Your work illustrates how technology, when grounded in lived experience and collective practice, can expand – not replace – human connection in language learning.

Ann

Thank you, Rob. For me, it always comes back to learners. Technology is just a tool, but access to it is a right. If we can use it to reduce barriers, increase flexibility, and support belonging, then it’s worth the effort.

KEYS helps job seekers of all ages and abilities, looking for a job or exploring career options; entrepreneurs with services designed to make it easier to pursue their business goals; employers by supporting their staffing, training, and retention needs; or newcomers to Canada requiring English training and settlement help.