Avenue Teammate Spotlight: Dr. Sepideh Alavi

Dr. Sepideh Alavi’s path to New Language Solutions spans university teaching, teacher education, and early work in computer-assisted language learning. Now Associate Executive Director, she helps guide Avenue and CanAvenue with a focus on thoughtful innovation, accessibility, and instructor-informed design.

In this conversation, Sepideh reflects on how her academic background, lived experience, and curiosity about technology shape her work and what that means for the future of language training and newcomer settlement.

Generative AI was used to help organize and edit the original interview transcript. It helped break long answers into shorter sections, add clarifying questions, and improve readability, while keeping the interviewee’s words, meaning, and perspective intact.

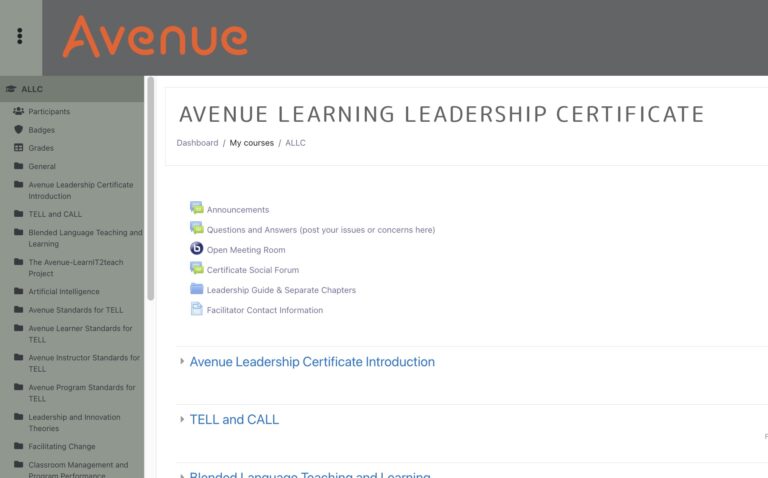

As I became more involved, I also started working on updating and improving training materials for the Avenue (LearnIT2Teach) Teacher Training Stages. That opened up opportunities to mentor and support instructors as they worked through the training themselves, which I found very rewarding.

Over time, those responsibilities expanded into broader leadership roles. I became the manager of CanAvenue, where I oversee course design and development for our independent language learning platform. More recently, I stepped into the role of Associate Executive Director at New Language Solutions, supporting the Executive Director with day-to-day operations and organizational planning.

Even early in my academic career, I was drawn to the potential of computers and online learning tools. At the time, technology wasn’t being used very systematically in language education, especially at the graduate level, and I saw a real gap there.

That led me to propose and develop courses in Computer-Assisted Language Learning (CALL). I designed the syllabi, secured departmental approval, and taught both the theoretical foundations and practical applications. Students worked with tools like Moodle, H5P, Hot Potatoes, and other authoring programs, so they could engage hands-on with technology they might later use as instructors themselves.

Running the school required me to manage the LMS independently, do some basic coding, and handle hosting and distribution of learning materials. It was very hands-on, and at times quite challenging, but it gave me a much deeper understanding of how learning technologies work behind the scenes.

We had to pivot quickly to an in-person model. We continued using the digital tools and materials we had developed, but not in the way they were originally intended. That experience – adapting under pressure, blending modalities, rethinking delivery – had a lasting impact on how I approach instructional planning and course design.

When the global pandemic hit and educators everywhere were forced to rethink how learning could happen, I found myself drawing directly on those earlier experiences. It still amazes me how closely aligned my past work is with what I do now at Avenue and CanAvenue.

I also find it very rewarding to see how language learning theories and research are translated into practice through digital materials. That connection between theory and real-world application is what excites me most.

It also supports inclusion by offering flexible, learner-centred pathways. People can participate at their own pace and according to their real-life constraints. For many newcomers, that flexibility is the difference between being excluded and being able to engage fully with their new community.

For educators, AI also has the potential to reduce administrative and preparation workloads, which can help restore some work–life balance.

At the same time, there are serious risks. Privacy and data security are major concerns, as many AI systems collect personal information. There are also ethical issues around transparency and appropriate use. We’re already seeing cases where people default to AI instead of doing the intellectual work themselves, producing content that looks polished but lacks depth or originality.

And of course, there’s the digital divide. Not everyone has equal access to technology or the digital literacy needed to use it effectively.

Used thoughtfully and creatively, digital tools can open up engaging, flexible learning possibilities that genuinely support both instructors and learners.